Virus Culture | Replication Structure

2002

text from a talk given at Chaos and the City

For those of you who haven’t been in a scientific classroom for a while, let me do a very quick refresher course on viruses and how they work. Please note that this refresher course is being given to you by a non-scientist. Expect poetic and theoretical interruptions of what is otherwise considered textbook material. If there are scientists in the audience, please roar in outrage at any bad science, but understand I am trying my best to navigate a complex field and that my particular brain type gets a kick out of trying to establish relationships between things like misrepresentation and mutation.

Viruses have a number of parts: the genome (either DNA or RNA), the nucleocapsid (proteins that coat the genome), the capsid (an outer protein shell) and the envelope (an outer lipid coat derived from the cell in which the virus replicates.) The envelope is not present on all viruses, and those that contain envelopes are usually less stable than those that do not.

Viruses replicate in six distinct steps.

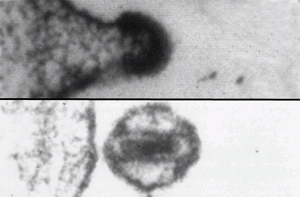

1. Attachment of the virus to the host cell surface. Attachment usually involves the specific recognition of a cell surface structure (a protein or a carbohydrate group) by a component of the virus surface.

For an infection to begin, there must be some kind of recognition between the infector and the infectee.

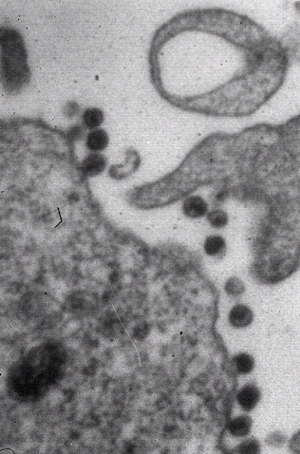

2. Injection of the viral nucleic acid into the host cell cytoplasm. Injection is often carried out by structures in a virus tail whose function is to get the nucleic acid into the cell. The viral container does not enter the host cell.

Injection = invasion. Alien information and structure is transferred to the interior of the cell by a specific device. The transporter mechanism does not participate in the invasion.

3. Replication of the viral nucleic acid. The parental nucleic acid is used as a template for synthesis of progeny nucleic acid molecules.

The host cell gives the virus directions for replication, it provides the plans and the structure for its own potential destruction and for that of its host.

4. Expression of viral genes.

This is an act of translation. Host cell structures are decoding and rewriting cites for viral genetic information.

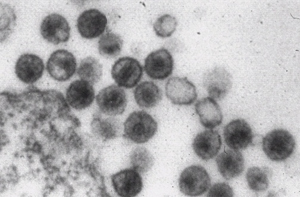

5. Assembly of progeny virus. Viral nucleic acid and proteins self-assemble inside the host cell to produce mature, infectious virions. Host cell proteins and nucleic acids are not usually included in mature virions.

The viruses become independent, the host is no longer necessary to nor physically included in their existence.

6. Release of mature virus from the host cell. This release typically occurs when the host cell disintigrates releasing hundreds of mature virions into the extracellular space. If a virus causes cell death, this cytopathic effect is seen in the whole animal…for example polio virus destroys anterior horn cells in the spinal column, causing paralysis. Some viruses do not cause cell death but instead provoke an immune system response in the host that is pathological or they transform cells, creating malignancies.

The host is no longer necessary and is discarded. The virus is teeming and free.

The image-type of this gap ad is sufficiently familiar to us that the logo can be minimized; the relationship between the company and the ubiquitous blue cotton shirt is established sufficiently such that any blue cotton shirt anywhere might be a sign for the gap.

Godin’s book was positioned on the back of another by Douglas Rushkoff called Media Virus. Rushkoff's contended that media viruses are not metaphors; they are viruses. He argued that the media can be perceived as an autonomous entity or 'other' in its own right, a single organism or sensory network of the planet. He postulates the 'hive mind' of humankind is reflecting and becoming aware of itself in the media, and that media viruses are mechanisms of correcting its faulty code. This code is made up of memes, ideas, behaviors, styles, or usages that spread from person to person within a culture. Rushkoff says these viruses can be constructed consciously; they can be 'bandwagon' viruses, as some interest group hijacks an issue (say the release of prisoners back into the community) for their own ends, or they can be self-generating, when society has hit upon a weakness or ideological vacuum.

The zoologist Richard Dawkins is usually credited with coining the term 'meme' in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. The idea of a cultural unit of information had been proposed by others prior, including sociologist Gabriel Tarde and Belgian essayist Maurice Maeterlinck and theorist Douglas Hofstadter. If you dig a bit, you find a lot more history for this little word and some interesting historical metapatterns.

Historical romance novelist Robert W. Chamber's short story collection The King in Yellow (1895) was the model for H.P. Lovecraft's Necronomicon, a fictional book that has inspired horror books and films, role-playing games, and rumor panics. Chambers' stories explore the unsettling psychological effects of a mysterious book that "spread like an infectious disease, from city to city, from continent to continent, barred out here, confiscated there, denounced by press and pulpit, censured even by the most advanced of literary anarchists."

George Gurdjieff's Beelzebub's Tales to His Grandson (1950) explored mythic constructs lingering beneath complex words constructed of combinations of Armenian, Russian, French, and English. Gurdjieff conceived memetics as part of a biopsychosociospiritual system, proposing the 'legominism' as a form in which "ancient wisdom is [culturally] transmitted beneath a form ostensibly intended for quite a different purpose." Gurdjieff suggested that these truths encompassed architecture, archaeological artifacts, dance, and mythic folklore. He believed that this knowledge was "not preserved in books but in the experiences of people."

William Burroughs theorized that language is actually a living virus, an organism that inhabits our thought processes. To Burroughs, when we speak, we are spreading a disease of thought control belonging to that virus. In the late 50's, Burroughs and artist Brion Gysin developed a method that they believed could defeat this virus, a method they called "cut-up". Apparently Gysin stumbled upon the technique while cutting pictures with a razor over a newspaper. Recombinations of the newspaper parts yielded new, and uninfected, meaning. While this kind of technique interested many artists before Burroughs, it is Burroughs’ belief that cut-ups were viral vaccines that interests me. Burroughs writes about viruses in a number of his books. Cities of the Red Night is an apocalyptic novel about a population afflicted with a radioactive virus. Burroughs said in an interview about this books that evolutionary change may be “biological mutation [over] one or two generations, possibly through a virus. No virus we know at present time acts in this way - that is to say, would affect biologic alterations, then genetics. But such a virus may have existed in the past.” And in The Place of Dead Roads he writes some pretty amazing passages, like this one:

“Now your virus is an obligate cellular parasite, and my contention is that what we call evil is quite literally a virus parasite occupying a certain area which we may term the RIGHT centre. The mark of a basic shit is that he has to be right. And right here we must make a diagnostic distinction between a hard-core virus-occupied shit and a plain ordinary no-good son of a Bitch.”