©

samantha krukowski

hands passing in the light

Text, Practice, Performance, No. 1

2000

I am looking through an old spiral notebook--the university seal on the cover is mostly rubbed off. The handwriting does not look like mine (my writing no longer slants) though it still has the same architectural regularity. There. In the back, on a few pages, the following notes:

- Ulay and Abramovic, Light/Dark, 1977

- 20 minutes slapping each other hard

- Domestic violence, qualities of challenge--challenge as a rhetorical thing in the west, audience discomfort

- Why 20 minutes? Desensitizing

- For a woman to slap--only a stall--not perceived as a real desire but instead as a sexual come on

- Man's slap--discipline: get hold of your hormones--curative--reinstating patriarchal order

- Element of torture--what's it going to be like to be slapped one more time? (Notes taken in Art Since 1950, taught by Dr. Robert Jensen at Washington University, St. Louis Missouri, Fall, 1991)

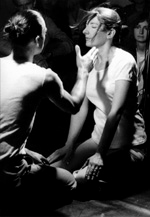

I shift out of the chair to a cross-legged position on the wood floor, notebook in hand. I remember there were slides projected while I took these notes. The one I recall shows the performers kneeling opposite each other. Were they wearing clothing? The picture depicts the moment where a hand (I do not know whose) is poised to hit. The photograph is blurred; behind the raised and threatening hand there is a whitish, sweeping trail. This ghost image emphasizes the imminence of an action, its trajectory. It sends the viewer looking for the place of landing, where there will be contact, and sound. The receiving cheek is a punctum (To Roland Barthes, the "punctum in a photograph is "that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me." My memory of this slide is focused on the receiving cheek--to me, it is the photograph's punctum. see Barthes, Camera Lucida, 27.) in this photograph, a tabula rasa that invites imaginative entrance. Even now, with nothing but the memory of the image in front of me, I strain to see the impression the hand leaves upon the cheek, the gradual reddening of the flesh; to hear the sound of its taut resistance and its reverberations.

- Light/Dark

- In a given space

- Performance

- We kneel, face to face

- Our faces are lit by two strong lamps

- Alternately, we slap each other's face until one of us stops. (Abramovic, Artist Body, 174)

Light/Dark falls into the category of artistic genres called performance art. Like most performance art events, Light/Dark is not dimensionally finite. It is no longer extant, its historical presence is dependent upon photographs and words, it is made with and by bodies, it represents a physical and emotional exchange, its components include memory, time, ritual and endurance. It invites methodological inquiry as much as it problematizes historical attention to artworks which leave no physical traces behind.

I was twelve years old at the time of Ulay and Abramovic's performance and not among the audience members who witnessed it. Had I been in the audience, I would not have seen Light/Dark in its entirety. My attention would have been selective. I might have focused on a particular aspect of the performance and ignored others. I might have been more interested in the audience members than in the artists. I might have been tired, bored, distracted. My presence at Light/Dark would have given me a spatial and sensorial memory that my absence denies me. But my attendance alone would not be the determinate factor in decoding the reception of the performance, or the wealth of associations and possible meanings it embodies.

Typically, when an author has not experienced something firsthand, that person relies on historical research and first-hand accounts to recreate and re-tell the event. Very little information remains about Light/Dark. The original audience is largely anonymous; their stories silenced by a lack of designation. There are two photographs which stand in for Light/Dark wherever it is mentioned (a third has appeared in recent writings). These are printed either in one of just a few articles about the performance, or in texts which consider works by Ulay and Abramovic or the works of artists whose work resembles theirs. Yet, the writing, stories, objects and photographs which constitute its meager archives do not represent it so much as offer a substitute body for an art form which has none. They attempt to stabilize what is inherently unstable about Light/Dark, and can only supply a ceremonial foundation for, not an extension of, the understanding of such works.

If I go in search of Light/Dark now, I will not find it. No matter how it (or its parts) has been historicized, the performance remains elusive. There is no single object called Light/Dark that can be understood to represent it in its entirety. An interpretation of Light/Dark (by someone who has or has not seen it) can only begin with a collage of its remnants. The meaning of the work is less likely to be found in the experience of its performance, the intentions of the artists or the reactions of the original audience than in the mapping of its elements and the discovery of the intersections and interstices which result.

That my translucent memory serves as the basis for a discussion allows my text to become a re-performance of Light/Dark; an action that rides on the back of an elusive and inspiring mentor but which also, occasionally, jumps off. Light/Dark is a "founder of discursivity." (Michel Foucault says that "founders of discursivity" are "unique in that they are not just the authors of their own works. They have produced something else: the possibilities and the rules for the formation of other texts." See Foucault, "What is an Author?", in The Foucault Reader, 114.) My role as author is conflated with that of an audience. I rely on indices that the performance itself may have never left behind in order to speak about it. A consideration of the piece coincides with its immediate extension and embellishment. Light/Dark provokes a response that is defined by the adumbral space where experience, thought, and imagination come to be called expression.

I remember Light/Dark first as a photograph. This is important, for photographs weight and dramatize a spectacle and confer upon it the status of a historical event. Photographs serve to memorialize Light/Dark and affirm its veracity (and importance) at once. The slides I first saw act like other photographs as a preservation of what Roland Barthes has termed the "That-has-been", the indication that "what I see has been here, in this place which extends between infinity and the subject...it has been here, and yet immediately separated; it has been absolutely, irrefutably present, and yet already deferred" (Barthes, Camera Lucida, 77). The moment of the performance is over, the performance occurred and will not reoccur, the performers will never be in that place or of that age again. There is an implication of loss in the image of Light/Dark that I know, and this sensation is doubled by the content of the piece. The performance is made heavier when it is contemplated as a photograph--it usurps some of the characteristics of photography. A photograph of Light/Dark gives the performance a concreteness and finiteness that directs interpretation. It invites a particular and more specific reading, a reading of replenishment that makes up for the void (the Death) (Barthes says "Death is the eidos of (a) photograph." See Barthes, Camera Lucida, 14) that it depicts. It is also significant that the photographs I remember are black and white, with no color to obscure the polarity of the shades. This opposition of hues heightens a series of dualities that is exemplified through the title Light/Dark: black/white, man/woman, pain/pleasure, love/death, anger/regret, inside/outside, public/private, action/pause, sound/silence.

Before the performance begins, the audience members engage in a kind of foreplay by settling into and acknowledging their environment. They mark their physical space by identifying with their designated seats: draped coats and arranged belongings become symbols of decoration and occupation that signify a certain level of ownership in a temporary environment. Whatever the audience members bring to the performance conditions their expectations, especially if they are accustomed to seeing similar actions. Programs focus their attention on what is to come. They are influenced by the content of the programs, which tell them about the performers, the history or the content of the piece. Audience members are preoccupied with themselves and their space, and they are made aware of the space of the performers and performance because that arena is physically separate (it is in front of or above them).

The space of performance usually divides the realms of public and private by differentiating the space occupied by the actors (the stage) from that of the audience (the seats). A line is demarcated between the illusory and the real; it provides a barrier that emphasizes the contrived and constructed arena of theater so that it is not misrecognized as that of life. The performance is a protected realm where anything communicated is softened by the fact of its artificiality. However, Ulay and Abramovic's proposed action challenges the distinction between the simulated and the genuine, art and life. It exposes them to each other and to their audience and conflates the divided spaces of performative activity. Light/Dark attempts to deny and even assault the given partition between performers and audience, stage and seating.

As Ulay and Abramovic walk onto the darkened stage, the quality of their entrance is weighted. The audience is fixated on them, on their expressions, their silence, the sound of their footsteps. The performers move to center stage and in silhouette, kneel opposite each other. A shoulder or knee pops and cracks, piercing the expectant atmosphere and sharpening the attention of the audience. Bright lights burst the darkness and turn silhouettes into profiles. If Ulay and Abramovic walk into the public space of their performance without clothing, as they do in most of their performances, they challenge it by forcing the private upon it--stripped of social garb and the hidden privacy that clothing silently provides, their bodies are in immediate contrast to the place where they appear. As in all performances where the body is considered the canvas, here the body is emphasized as such. It is primed and ready to receive marks. Ulay and Abramovic's bodies may be contemplated at first as bodies (with notable body parts), but the tension and discontinuity created by their appearance will eventually dehumanize them so that the hair that covers them or the genitalia that jiggles on them will be less interesting than what happens to them. These bodies look like other bodies, but they will not do what other bodies which resemble them do. They quickly become sites rather than sights, and this transition precipitates an involvement on the part of the audience that further helps to diminish the performers' corporality.

For the audience, any sense of safe separation from the events they have chosen and paid to see evaporates immediately after one of the performers has been hit. (The distance between the performers and audience is not only denied in terms of physical space but because the audience allows the acts which are presented to them. Because of this unspoken consent, what results is not only a conflation of "public" and "private" but a blurring of what is seen and what is being performed. Kathy O'Dell deals with this problematic extensively in "Body & Text in Performance Art of the '70s: Prolegomena to a Psycholegalistic Approach to Art History" (Paper delivered at the University of Texas at Austin, 28 October 1993). Whereas they may have been initially comfortable in their seats, they encounter an increasing sense of discomfort. The surfaces that support them are suddenly noticeably hard and strangely anthropomorphized: these support guilty parties who wish to deny their increasing sense of responsibility. The audience members are made acutely conscious of their ability or inability to do something about what they see, and about the implications of making or not making an active decision.

Scarry explains that "just as all aspects of the concrete structure are inevitably assimilated into the process of torture, so too the contents of the room, its furnishings, are converted into weapons" (Scarry, 40).

The audience members and the chairs that support them, the dingy curtains and the stage that provides the buttress for the activity that occurs upon it, the chairs that keep Ulay and Abramovic in front of each other--all of these can be understood to be mechanisms of the performance which in some way cause the pain that is being exchanged. As the audience becomes conscious of its complicity, the engagement of its members shifts enigmatically and noticeably from spectatorship (detached observation) to voyeurism (observation marked by a desire for limited participation in something scandalous or sexually suggestive.) This voyeurism is about power: as in situations where documentary photographers record traumatic events rather than interfere in them or where people help a crime victim out of curiosity or hope for personal recognition if they decide to get involved at all, the audience members of Light/Dark are empowered with the ability to interpret and intrigued by the situation that faces them. They may be troubled by the character of the events with which they are presented and know that the actions they are observing violate certain codes, yet they simultaneously want to guard their ability to watch without interfering and their right to be entertained.

The audience members have a voice that is denied to the performers, whose language is diminished as their bodies are emphasized. Scarry writes that "intense pain is...language-destroying: as the content of one's world disintegrates, so the content of one's language disintegrates; as the self disintegrates, so that which would express and project the self is robbed of its source and its subject (Scarry, 35). As the performers hit each other, they exchange pain and deny themselves language. Even if the reciprocity of the performers' actions creates a capacity for communication between them, the first slap transfers the power of the linguistic sphere to the audience members, who use it to define the meaning of Light/Dark for themselves. As the performers lose their voices, the audience becomes more deeply embedded in the creation of its own narratives.

Pauses in the action focus the audience on events that occur in these voids. There are unexpected contributions: the rustling, whispering and coughing of the audience punctuate the performance like a series of rebuttals which may or may not cause the performers to respond. Unpredictable noises indicate an unusual and unnoticed communication between the players and the spectators which influence both to act or feel differently at any given moment. Shades of John Cage's 4' 33"; the audience for Light/Dark unwittingly participates in the performance they have come to see. (John Cage's four minute, thirty-three second piece, first performed in 1952, was a symphony of silence. According to David Revill, "anyone who listened would have heard the wind in the trees...rain blown onto the roof, and, in due course, the baffled murmurs of other audience members." See David Revill, The Roaring Silence, John Cage: A Life.")

A situation of domestic violence usually has an aggressor and a victim. Where Light/Dark is exemplary of such a mode, it blurs the identification of these roles. Whoever undertook the first blow might be identified as the aggressor, but the pattern of exchange that follows and the eventual desensitization that it causes obscures this first characterization. The structure of reciprocal slapping may be seen as an equalization that overturns stereotypical assumptions about the meaning of slaps delivered by a man or a woman. Historically, a woman who hits a man has been represented as out of control and weak, her slaps understood as sexual advances by the man being slapped (This stereotype is enacted across media and historical time period. See Myrna Loy in "The Thin Man" film series, Scarlett O'Hara in "Gone with the Wind", Kirstie Alley in television's sitcom "Cheers", Nicole Kidman in the stageplay "The Blue Room.") A man who hits a woman has been portrayed as engaged in a curative activity--his slap constitutes a dose of reality for an hysterical woman. Light/Dark calls into question whether physical violence can correct or change situations and people. The role of physical violence is certainly dramatized in the sphere of torture, where medical terminology and techniques are usurped to implement the very wounds they profess to heal. Scarry points out that various punishments have been composed of misdirected treatments including "unwanted dental treatment" and "overdoses of lethal drugs." Torture chambers have been called "operating rooms" and those meting out the suffering have taken names like "the mad dentist" or have actually used doctors as assistants to stabilize their victims so that they can endure more pain (Scarry, 42). Light/Dark undermines the way in which such slaps have been understood as corrective mechanisms (implemented by one person on another) by incorporating them in a reciprocal exchange. (It would be difficult but interesting to determine exactly how much time must pass before the audience or performers become desensitized by the repetition in the piece. Such determination would vary by performance and this variation would distinguish each one as "unique.")

The solidity and character of the domestic sphere is brought into question by Ulay and Abramovic's actions, but the effect of this implied disintegration is unclear. The audience wants to understand the performed actions as if they are real or connected to an identifiable history and situation. Ulay and Abramovic deny an implicit reading. There is no identifiable motive for the pain they exchange and there is no emotional or vocal response to it. There is no explanation for the increasingly bruised skin, the recoiling heads, the echoes of the sounds of hands colliding with bodily surfaces. The absence of a motive aids the audience in its voyeurism and linguistic power. In torture situations, "Displaying the motive...enables the torturer's power to be understood in terms of his own vulnerability and need. A motive is of course the only way of deflecting the natural reflex of sympathy away from the actual sufferer." (Scarry, 58) The audience avoids its responsibility to interfere in a situation where pain is being caused. Its members evade the reasons which motivate them to keep their eyes on the performers and enable them to watch in ignorance of the reasons the performers are carrying such actions. Their ability to objectify the situation with which they are presented would be challenged with more knowledge. Likewise, if either performer revealed to the other their exact motivations for hitting, allowing themselves to be hit, or their reactions to being hit, he or she could be unable to continue. For both the audience and the performers the arguments, accusations and screaming which traditionally accompany or precede physical abuse are absent. An energized arena exists for an imagination to fill in these predecessors.

Light/Dark gradually denies spontaneous emotional responses. As the piece proceeds it becomes more predictable--no new actions are introduced. The slapping turns monotonous. Looking away from Ulay and Abramovic causes the sound patterns to change, evolve. The time between hits varies. Too much time causes anxiety: when will the next come? At some point, the performers' skin grows numb, their hands sting, their arms ache. Their bodies begin to contort, their posture changes. They become accustomed to the structure of repetition and bodily remove themselves from the situation. The audience no longer concentrates solely on the performers; its members lose concentration. They hear the resounding slaps but begin to daydream in their rhythm. Only a variation in the rhythm of the slaps, a change in cheek color or some other disruption will sharpen the audience's diminishing vigilance. Narrative-making slows down.

Given that the body itself is usually a safe haven--"its walls put boundaries around the self preventing undifferentiated contact with the world" (Scarry 38)--when it can no longer control or respond to its experiences it too becomes a weapon against the person it houses. Ulay and Abramovic use the destruction of the unified body to explore its sadistic and masochistic overtones. (Future research could take into consideration the power and negotiation inherent in sadistic and masochistic acts, since Ulay and Abramovic have a contract between themselves in their agreement to perform the piece.) Exposing themselves willingly to physical pain, they deny their natural flight responses and become torturers of self and other. Such shifts in loyalty undoubtedly provoke veiled responses in the performers.

Ulay and Abramovic may initially be stunned by the pain they receive and deliver. They may want to stop it. They may want to continue, pushing the experience of doing something aversive to its limit. They may discover an unexpected aggression towards each other. The slaps may incite previous anger or begin to produce it. Since unexpected reactions are hidden, Ulay and Abramovic undoubtedly share a series of private notations which are invisible to any audience. The artists think their bodies and faces are communicating. Their eyes reveal complex reverberations which confuse or disturb the person who is to hit next. The blankness of their faces, as read by the audience, contain decipherable scripts. Ulay and Abramovic may also hide from each other in vocal silence, usurping the power provided by that void, privileging the denial of response, and using it to revel in the distance between them and their ability to withhold a reaction that communicates anything at all. Perhaps at the end of the performance they feel closer to each other for surviving what they impose upon themselves.

The actions of Light/Dark challenge a series of assumptions. They call into question the stability of any human union. It violates the spatial safety of "home" and the domestic sphere. The performance makes public the private status of domestic violence. It takes a generally one-sided act and makes it reciprocal, giving each side equal time and emphasis. It imposes stasis on an activity which would normally motivate flight. It denies emotion in the face of pain. It plays on the dividing line between sensitization and desensitization. My examination of this piece is premised on my desire to imagine and at the same time, to know what happened.

No longer is there an emphasis on the conflicts presented by the performers' actions. These actions become separated from the performers entirely as do their products. The source of this discovered beauty is no longer important. The moment Light/Dark becomes a symphony of sounds, the performers are only instruments which determine when the piece is finished. And when it is, the audience finds itself clapping, obliterating the sounds of the slaps.

My approach assumes that the meaning of an artwork is not located only in certain facts about it, but also in the variety and extent of the responses it engenders. Light/Dark is an artwork that no longer exists, and because of this its place in history is not claimed by its physicality but by a set of documents which are understood to record it. These documents--photographs, memories and descriptions--are once removed from the work in question. Interpretations of these documents are twice removed, and the text which includes or organizes them moves yet another step away from the "original" artwork. I accept this scenario of distances, and use it to construct a narrative which is comfortable telling a history in something akin to a novelistic voice. This action undermines an historical attitude that the role of history is to exhume extant stories and arrange their certainties in a recognizable form. I presume that history is something which is made, and that the historical contribution of any text is less dependent on its subject than on the attitude which is taken toward it.

I put the notebook down and begin to scan my bookcases for a book which contains images of Light/Dark. Too many colors, too many examples of graphic design. Aha. Upper right corner. Red glossy cover, tall hardback book. Heavy. I slide it out.

Turning the shiny pages, I pass images of Ulay and Abramovic, nude, facing each other in the doorway of an art gallery as visitors push through. Of the performers, nude, slamming their bodies together. Of the two, nude, walking forcefully into walls which move or which do not. Of the artists, clothed, back to back, with their hair tied together (they sat for 17 hours).

And here is Light/Dark. My memory serves incorrectly. They wore clothing. But their actions denied them vestments.

References Cited

Abramovic, Marina. 1998. Artist Body. Milan: Charta.

Abramovic, Marina and Ulay. 1980. Relation Work and Detour. Amsterdam: Idea Books.

Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Barthes, Roland. 1974. S/Z. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Battcock, Gregory and Nickas, Robert, eds. 1984. The Art of Performance: A Critical Anthology. New York: EP Dutton.

Case, Sue Ellen, ed. 1995. Cruising the Performative. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1984. What Is an Author? In Rabinow, Paul, ed., The Foucault Reader, pp. 101-120. New York: Pantheon Books.

Goldberg, Roselee. 1988. Performance Art: From Futurism to Present. New York: H.N. Abrams.

Lippard, Lucy. 1973. Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966-1972. New York: Praeger Publishers.

Montano, Linda. 1995. The Performance Bible. Austin: Booklab.

Revill, David. 1992. The Roaring Silence, John Cage: A Life. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Scarry, Elaine. 1985. The Body in Pain. New York: Oxford University Press.